The Poles at Albuera

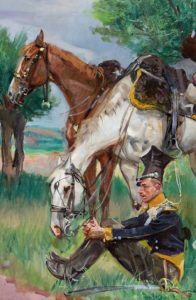

Here are two accounts of the battle of Albuera by officers in the  Vistula Legion lancers. Both accounts were translated by Mark Tadeusz Łałowski and edited by Jonathan North.

Vistula Legion lancers. Both accounts were translated by Mark Tadeusz Łałowski and edited by Jonathan North.

The first account is by Kajetan Wojciechowski, 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st Lancer Regiment of the Vistula Legion, and it describes the participation of his regiment in the battle of Albuera. It is an extract from Pamiętniki moje w Hiszpanii; first printed in 1845 (Warsaw), and reprinted in 1978 (Warsaw).

On the afternoon of 15 May 1811 we came across a huge, dense forest, through which the dragoons advanced as skirmishers whilst we pushed along the road through the middle. On the other side of the forest we saw the village of Albuera, on the right bank of the river of the same name, and with the bridge leading to it. Beyond the river the hills stretched towards a vast range of rocky mountains, and we observed that large numbers of infantry, dark masses of cavalry and artillery and a chain of outposts and pickets had been drawn up waiting. Then the sun began to set, and we, having established our camp, lit our fires. Of all the evils endured by the cavalry the very worst is when the horses are tired of riding and starving of hunger. I was just contemplating such sad realities, staring at the fire, when the order came to be ready at dawn for an inspection by our commanders. Having eaten a piece of rotten meat with my comrades and having drunk a glass of brandy, I fell asleep calmly.

At dawn on16 May, the trumpets sounded the reveille; I jumped up and was already at the head of my brave boys, when I heard the command: “Platoons, prepare to advance, by the right, walk”. While we were parading around the Marshal [Jean-de-Dieu Soult] as he stood in the centre, the sun began to rise. Our Colonel [Jan Konopka] shouted: “Flankers, forwards”! Riding past him, I heard the command: “Lances upright, advance to the left of the bridge, swim the river, attack the enemy”! Our platoons were moving off at a gallop, and I stopped for a while, listening in case of further orders. Then the colonel shouted at me in French, “Are you deaf ?” In a flash, I turned my chestnut horse around and was first to throw threw myself into the river. Near the bridge we saw some enemy engineers.

On the far bank of the river I formed up the platoon which had followed me, whilst [Peter] Rogojski did the same. We were then attacked by a squadron of London [sic, possibly Long’s 3rd Dragoon Guards] dragoons and routed them. Two other squadrons came up against us, and we started to withdraw in good order seeing Captain Leszczyński behind us at the head of two platoons of flankers and the regiment attempting to form on the right side the river. So we turned and hit the English again and the two squadrons that had tried to follow us were also crushed. It was only when overwhelming force came up against us that we began to encounter difficulties. Each of us began to fight with a few dragoons, and this uneven duel continued for quite some time when our artillery took up position and began to hit the English. Seeing how many of their corpses begin to litter the battlefield, the enemy dragoons yielded and withdrew.

Seemingly abandoned, and having fought in a protracted melee against overwhelming enemy, I asked Sergeant Rogojski: “Peter, have you anything to drink here?” He grabbed his flask, took a sip, and handed it over to me. Just then, as I was drinking, a cannon ball flew between us, having been poorly aimed by our gunners, missing us by a hair’s breadth. The English saw that no one had arrived to assist us, so they attacked us for a third time. When we noticed that our supporting troops had fallen back and the regiment on the right side of the river was no longer visible, I called on Rogojski to cross the river immediately and open fire from the other bank. To our misfortune, the horse being ridden by the corporal from Rogojski’s platoon slipped on the muddy ground by the river bank, and held them up for some time them. Meanwhile, surrounded by attacking Englishmen, and having lost 14 men from my platoon, and with a saber in my hand we retraced our steps and throwing ourselves into the river, were glad to reach the other bank. On that side of the river Piotr Skrobicki, a regimental adjutant, suddenly appeared informing us that he brought orders for us to go back for a third time, but we did not listen to him. The commander of our squadron [Telesfor] Kostanecki rode up after him and said: “And so, is this the authentic gentry of Poland: waving sabers, cheating death, and ignoring orders?” Having explained to him that we had not yet received any orders, we then followed him until I saw that my horse was lame in the leg. A good creature, which, despite being injured, saved my life. As we trotted along the river to the place our regiment had initially been positioned, we caught sight of a naked corpse. It was our poor [NCO] Jagielski, the first bullet fired had hit him, and thus he found the death he had himself foretold. We lost Captain Leszczyński in this sad expedition; hit by a bullet, he died few days later and was buried in Llerena. Having rejoined the regiment, we found the Spaniards, Portuguese and English under the command of Marshal [William Carr] Beresford drawn up in combat formation and ready for the battle. The enemy army rested its left wing on the village of Albuera, stretching its line along some heights which ran from Santa Martha and which began rather steeply before dipping as they neared Olivenza and Badajoz. At the foot of this position was a small river Albuera. The right wing was occupied by the English, whilst the Portuguese and Spanish took up positions in the centre and on the left. Marshal Soult, having studied the enemy position, concluded that it would be impossible to attack all along the line with his meagre forces. He therefore elected not to divide his forces, but decided instead to launch attacks against selected points. General [Nicolas] Godinot was ordered to seize the village of Albuera, firmly held by the Spaniards, whilst the V Corps, commanded [temporarily] by General [Jean-Baptiste] Girard, was to attack the English, or the enemy’s right. General [Victor] Latour-Maubourg with 3,700 cavalry men was detailed to support him and, after over-running the enemy positions, to pursue the routed Englishmen. All these maneuvers were supposed to take place under the cover of the French artillery commanded by General [Charles] Ruty. A light artillery battery was left however to General Godinot and it was this battery which opened the battle in the morning of May 16th. General Godinot crossed the river and opened heavy fire on the village of Albuera while General Girard struck the enemy’s right with determination and energy and forced the English [Stewart’s 2nd Division] into a slow and orderly retreat towards the middle of their position, which they sought to strengthen by this movement. Having seen their manoeuvre, Marshal Soult ordered our regiment [the 1st Regiment of Vistula Lancers] to attack them in their flank. We set off in preparation for this attack, but we had a wide ravine to cross, and so had to then form up in sight of the enemy’s line before finally striking them in squadron formation. Having scattered three English infantry regiments [Colborne’s Brigade], we took 1,000 prisoners and six guns, and after repulsing an attack by London [probably meaning Long’s] Dragoon Regiment, we returned to our former position.

Meanwhile, General Godinot was still engaged against Albuera, and had not managed to drive the Spaniards [actually it was the Portuguese and Germans] from the village; General Girard, however, stormed the British position with bayonets fixed. This initial success was very costly, for we had two generals killed [Werlè and Pepin], and three wounded, and there were battalions in which not a single officer remained. After this first attack, V Corps was on the point of rolling over the second and third enemy lines but lacked the strength to do it and therefore our infantry, quitting the positions they had just occupied, began to withdraw slowly, with the English following them. Then General Ruty, having concentrated all the artillery, opened a murderous fire, which, over the course of several hours, caused a great deal of damage in the enemy ranks. General Godinot retreated from Albuera and Marshal Beresford, having noticed the hesitation in our ranks, wanted to throw all of his infantry against us in order to decide the fate of the battle.

It was then that Marshal Soult appeared in front of our regiment and shouted: “Colonel! Save the honour of France!”. So [Colonel Jan] Konopka ordered an attack, we fell on the enemy [Cole’s division], whom we stopped in their tracks for some time, winning time for General Latour-Maubourg to move forward and frustrate their intention to do us harm. The English in their reports, described the battle of Albuera, and mentioned our regiment : “The Poles started the battle, continued it and concluded it with the greatest glory.” Later our colonel was promoted to the rank of general. We received 11 crosses of the Legion of Honour for our Regiment, and I finally received one too, for the loss of 3 horses killed under me, and a sword cut and the wound from a musket shot which I also received. We lost five officers killed and 11 wounded in our regiment and 200 soldiers wounded and killed at Albuera.

This account is by Captain Jakub Kierzkowski, aide to the cavalry commander General Latour-Maubourg and it describes his participation in the Battle of Albuera, 25 km from the fortress of Badajoz on 16 May 1811. It was published in Pamiętniki J.F. Kierzkowskiego, Warsaw, 1903.

Marshal [Adolphe] Mortier received orders from Paris to return to France to take command of the Young Guard, and thus the command of V Corps passed to General [Victor] Latour-Maubourg. General [Jean-Baptiste] Girard was left in Badajoz with 6,000 troops, while Latour-Maubourg taking the rest of V Corps returned to the town of Llerene. Shortly afterwards the English under Wellington came up and imposed a blockade on Badajoz for good, attempting to approach the fortress using those same trenches and tunnels that we had made use of and which it had proved impossible to destroy in time. Marshal [Jean-de-Dieu] Soult hurried forwards to drive the English from Badajoz, gathering 22,000 troops and taking Zafra and Santa Marta, a mile from Albuera, where the English had already taken up their positions [with 36,000 English-Portuguese-Spanish troops]. Marshal [Auguste] Marmont, with his corps, continued his march to assist us at Albuera, but Marshal Soult did not wait for Marmont before engaging in battle. It started with great fury. Throughout, I was placed at the disposal of General Latour-Maubourg, who commanded the cavalry. Once the army was deployed, with some regiments remaining in reserve, he sent me to Colonel [Jan] Konopka in order to place his regiment to the left of the 10th Hussars. I immediately conveyed orders to Colonel Konopka to trot forwards, and wanted to go back to the general in order to report to him that Konopka was advancing. However, the colonel requested that I take him to the specific position, which I did before galloping back to General Latour-Maubourg with news that the regiment was now in position. The British artillery was now starting to hit the French cavalry, and their infantry was bravely advancing with the bayonet against their French counterparts. The left wing of the French infantry began to yield, whilst the French right pushed back against the English. Just then, General Latour sent me to Colonel Konopka, who was not then present with the regiment, ordering that one squadron of uhlans [lancers] charge the rear of the English infantry at the canter. The commander of [Telesfor] Kostanecki’s squadron fell on the British infantry, and took the entire battalion prisoner along with their standard and four cannon. The British sent a squadron of hussars against the Polish lancers, but they did not dare attack, seeing a fresh squadron of the uhlans moving up in support. The cannonade grew more intense, a roundshot glancing under my horse, smashing my stirrup and wounding my leg. My horse collapsed and trapped my leg and I could not pull it out or get free from the horse until a captain of the 10th Hussars had me pulled out and so, soaked in my horse’s blood, I mounted a mare taken from a killed hussar. Unfortunately she had been wounded between her ears with a pistol shot, and so I did not ride very far because she soon collapsed and died . Despite of oppressive heat, I managed to drag myself back to the road to Seville, where I found my servants and spare horses. I changed my uniform, kept one boot on one leg, and wore a slipper on the other, and mounted another of my horses. Evening was coming, Marmont had not arrived and the army remained on the battlefield. It was not until the third day that Marshal Soult, lacking food for the army, was forced to fall back on Seville, and on Marmont’s corps at Traxico. The English lost a lot of people at Albuera, especially from their cavalry. The Polish cavalry defeated their cavalry in each attack, because the English horses feared the pennons of Polish lances, so their horses always turned and fled, and the Poles stabbed them from behind. Many of the English complained about the conduct of the Polish lancers as they deployed their lances effectively when in pursuit. Returning to the battlefield of Albuera our corps rested there and I went to see the place where my horse had been killed, but I found only ashes because the English had ordered that dead soldiers were to be buried and dead horses burned, to ensure that the air was not infected. In this terrible heat, I felt a great desire to drink and I approached the stream through which we had passed when advancing to battle and drank a cup of water. It looked like a clean spring, and I was tempted to drink again, swallowing a second time when I suddenly noticed the corpse of a dead soldier with a wound from a musket or bayonet in his side and partially hidden by the branches of a tree. I was immediately sick, was struck down by fever and falling ill was forced to go to Seville for treatment. I remained ill there for almost one and a half months.

[A few months] later, Marshal Soult received a message that several thousand insurgents had landed near Gibraltar and were advancing through the mountains towards Seville. Then Marshal Soult sent orders to the corps of Generals [Claude] Victor and [Horace] Sebastiani to dispatch one infantry division each, sending them along the [Mediterranean] coast, one from Cadiz, and another from Ronda in order to cut off the insurgents. From Seville he also sent a reserve under General [Nicolas] Godinot, who was to advance so that he would blockade Gibraltar, whilst these two divisions intercepted the enemy. I had recovered by then and could therefore be of use to General Godinot in this expedition. General Godinot force-marched his division and so we were first to encounter the insurgents pushing them back before us towards Gibraltar, with the two other divisions arriving a few hours later. However, ultimately, the expedition was not a success and the generals returned their divisions to their original positions. When we quit Gibraltar for the town of San Roque, all the inhabitants fled and when my servant brought the horses into a building’s courtyard there was not a living soul, only some birds, song birds and monkeys attached to chains and all very hungry especially the poultry which had nearly starved. I was initially with General Godinot outside of the town at the place where our troops had taken up positions. Later on the general rode into San Roque, and was billeted at the English inn. I also arrived to see my servant, and obtained food for the birds and a monkey, and fed them, watching the monkey fawning and behaving with absolute charm. When the time came to leave San Roque I accompanied General Godinot, and it was my servant who led the horses and carried the monkey to the horse, which also bore my two small bags. He placed this monkey on the horse and tied it to the saddle but when we started crossing through the mountains, everybody had to dismount and lead their horses. Our monkey slipped down on the horse’s neck and started to pull his mane, the horse shook his head and the monkey found himself between the horse’s front legs. Of course the horse was terrified, and began to buck, and almost fell from the high mountain. The saddle girth broke, the bags fell to the ground, and the monkey, too. I ran up to it, grabbed the servant, and ordered that he let the monkey go into the mountains in order to avoid any further misfortune. After our arrival at Seville, Marshal Soult, angry at General Godinot for having failed to carry out his plan for the expedition, ordered that a court martial try him. Without waiting for the verdict, the general killed himself. At 3 o’clock in the morning, he ran down to the sentry post and brought a soldier’s musket back to his room, put the barrel in his mouth, and with his foot he pulled the trigger so that his head was blown off and his brains splattered across the walls. General Godinot was 70 years old and was once a hero, but he was unfortunate in that he liked to drink so much despite his age. Almost all the time we marched along he was summoning his servant Garyg and getting him to bring him a bottle. After this expedition I returned to the headquarters staff of Marshal Soult.

Notes on the authors

Wojciechowski, Kajetan (1786-1848), enlisted 15.1.1807 in the Hussars of Franciszek Sułkowski, as a corporal. 1.9.1807 promoted to the rank of Staff Sargent. In Kassel he joined the Vistula Legion Lancers on 1.1.1808, promoted to the 2nd Lieutenant on 29.6.1810. Wounded on 16.5.1811 at Albuera, received Legion of Honour on 6.8.1811. He quit the regiment in Spain on 6.10.1812 and went to the depot in Sedan. By the end of January 1813 he was reportedly sent to Duchy of Warsaw to recruit new soldiers for the regiment. In Saxony in 1813 he was promoted to lieutenant (19.6.1813), but following the surrender of Dresden on 11.11. 1813 he was taken prisoner.

Kierzkowski, Jakub Filip (1771–1862 ) enlisted in the Polish army in August 1788, serving as a cadet in the 1st Royal Regiment. A year later he was a corporal and he took part in the Polish-Russian war of 1792 and in the so called Kościuszko Uprising of 1794. He fought at San Domingo in the Legion of General Charles Kniaziewicz, and in Prussia and Poland in the years 1806-1807 on the staff of Marshal Jean Lannes. He was in Spain between 1808 and 1812 and took part in the 1813 campaign in Prussia and the 1814 campaign in France. He also participated in the 1830 Polish November Uprising against Russia.

- Poles during the Napoleonic era

- A critique of Poles

- Rudnicki's Peninsular War

- Fuengirola

- Two lancers at Albuera

- Soldiers of Misfortune

- 3rd Guard Lancers in 1812

- Napoleon's Police

- Nelson at Naples in 1799

- Napoleon and Saint Domingue

- The Death of Murat

- Napoleon in Russia

- Ireland in the 1790s

- Napoleon and Egypt

- Prisoners of War (1792 to 1815)

- Travel in Napoleonic Europe