1794 in Naples

The French Revolution came as a shock to the kingdom of Naples. The queen, Maria Carolina, was, after all, Marie Antoinette’s sister, but the king, Ferdinand, always a little paranoid, was also profoundly disturbed. So too was their chief minister, the archly conservative Giovanni Acton. Whilst the events of 1789 were bad enough, the Terror positively shook the Bourbons of Naples to their core, even more so when France signaled that she would work to export revolution across Europe. Italy, which had spent a century in decline and longer in an abusive relationship with its rulers, boasted a good number of ardent reformers and sympathizers who seemed ready to raise the banner of revolution. Naples was no different and, following a decisive French victory at Toulon, where a young Napoleon Bonaparte distinguished himself, a so-called Jacobin conspiracy was discovered in Naples in the spring of 1794. It was a pre-cursor, a trial run, to the greater revolution of 1799, but it too generated its fair share of martyrs and exiles.

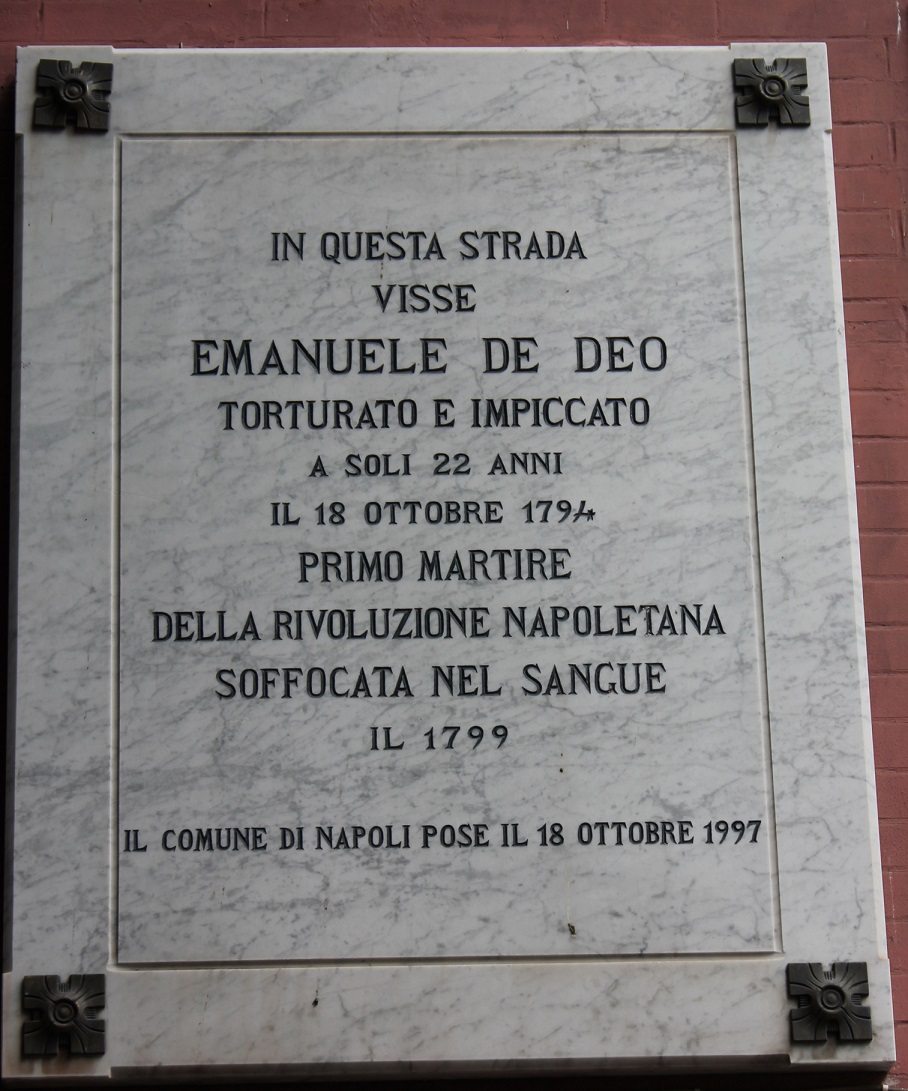

The plot was more of a reactionary scare to a series of actions deemed revolutionary. The only act of treason the police found or manufactured had centered around Andrea Vitaliani, who was supposed to have planned to seize control of the city’s castles and then kill the king and queen. However, his real crime was of having conspired to produce an Italian version of France’s 1793 constitution, which was then printed by Giordano at the cost of ‘30 or 40 Ducats’. A copy is rumoured to have been placed on the queen’s table with the note ‘like it or not, this is what must be done’. His brother, Vincenzo, aided and abetted him, whilst all Emanuele de Deo managed to do was rather flamboyantly stab a portrait of the king with a table knife during a revolutionary banquet at Posillipo. Tommaso Amato, who was also arrested in the round up, this time for profanity and blasphemy. A British tourist, Nelson Brooke, found himself caught up in some of the drama:

“21 April, 1794

I had been here only a few days when notice was given to the inhabitants to retire to their houses as an insurrection was announced by the threats of a man who was that day to be executed. His crime was for having entered a church while the priest was elevating the host at high mass, he called out and desired him not to deceive the people by such ceremonies, making use of blasphemous expressions, and also saying that the King of Naples would soon be deposed, and the country freed from tyranny.”

The plotters were arrested or scattered into exile, the regime hitting back against the revolutionaries by establishing a grand Giunta di Inquisizione to try opponents and hound dissent. Brooke continues his account, and Amato’s appearance before this court and that scaffold:

“He was seized on, carried to the prison, and publicly tried. He repeated to the judges what he had before said, adding that he himself had once laid in wait for the king to assassinate him. And though it did not then take place, it would soon be effected by others. The judges ordered him to be taken out of court and confined as a madman, but he persisted in saying that he was in perfect senses, and demanded his sentence [be carried out], which was to have his tongue cut out, and his body hanged and burnt. He then boldly asked the judges if his tongue was to be cut from his mouth before or after his death; on being told the latter, he said that when brought to the gallows he should inform the spectators what they ought to do and that a great number of accomplices would join them, not only to rescue him from death but to complete a revolution. He was born in Palermo had been bred to the law and would have no advocate to assist him at his trial. All the troops in and about the city were ordered to attend his execution. He walked from the prison to the gallows with a piece of wood fastened to his mouth. The two priests who attended him at every step exhorted him to repentance, and to discover his abettors, desiring him, if he assented, to incline his head and he should receive a pardon. But he continued obstinate and made signs that they should conduct him to the place of execution where the sentence was performed without any disturbance.”

Vincenzo Vitaliani, Andrea’s brother, and Vincenzo Galiani also went to the scaffold in October, as did Emanuele de Deo who, after being tortured in an attempt to get him to reveal who else had been present at his revolutionary banquet, was executed on 18 October 1794. Meanwhile, the British envoy to Naples, Sir William Hamilton, was relieved that these revolutionary tendencies had been purged adding that ‘I hope in a few days and by a few executions all will be quiet again’.

All was quiet, at least for five years. Then the French armies arrived, the Bourbons fled and Naples had its revolution. The martyrs and exiles of 1794 would have their brief revenge.