On Christmas Eve 1800 a bomb went off in the streets of Paris. It had been designed to kill Napoleon Bonaparte as he travelled from the Tuileries Paris to the opera house. His coach had been driven down his usual route, exiting the Tuileries courtyard into The Carrousel then passing down the badly paved Rue Saint-Nicaise and turning right into the Rue de Malte towards the Théâtre des Arts et de la République in the Rue de la Loi. But, on the fateful evening, at around a quarter past eight, a cart stood at the corner of Saint-Nicaise and Malte, and a hackney carriage was blocking the only way through. The First Consul’s driver reined in his horses whilst the Consular Guard escort, riding ahead, forced the hired cab out of the way. The coach then continued on its way but, as just after it had turned the corner, a huge explosion engulfed Saint-Nicaise, scattering body parts, glass, roof tiles and timber in every direction. The cart, the first vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), the first car bomb if you will, had found its way onto the streets of Paris and into the history of Europe.

Napoleon, who had made himself First Consul of France just over a year ago, survived but the atrocity sparked a hunt for those who had been behind a crime which, whilst failing to behead the government, had killed and wounded scores of innocent Parisians. It presented a baffling case for the police of Paris, under Prefect Dubois, and for the political police of Minister Fouché, but it also presented an opportunity for the young, insecure new regime of Napoleon. He made full use of it, swooping against his political opponents from the days of Revolution, whilst simultaneously discrediting the agents of the exiled king as being the hired hands of perfidious Albion. As the witch-hunt continued the detectives also set to work and they were soon on the trail of a radicalised network of assassins who, whilst they had failed this time, were quite prepared to strike again and to rid France of her new usurper.

It was one of the great crimes, and the greatest of stories, in French history. And today, the act itself, and the divisive aftermath, resonate strongly in a Europe where peoples and governments are coming to terms with a new age of terror.

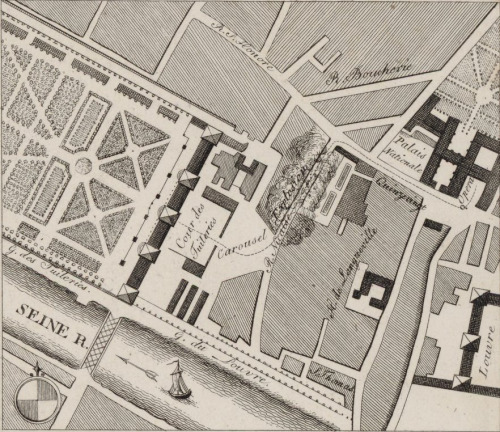

This is often cited as the scene of the crime:

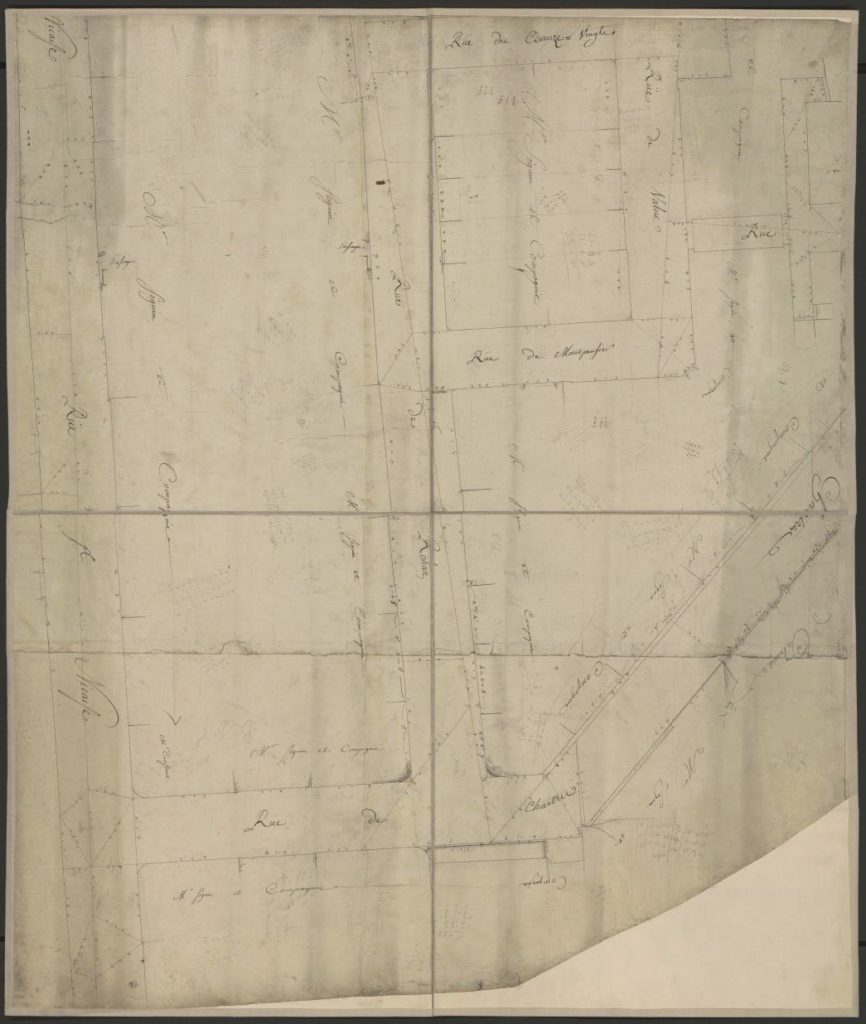

But, in fact, this is inaccurate. The bomb went off beween the Caroussel and Rue Hoche, a sidestreet which is not shown on the map above. This is significant because Napoleon’s coach turned into that sidestreet a second or two before the bomb went off. This probably saved him from serious injury, perhaps even death. Here is a better plan with Rue Nicaise running down the left-hand side and the sidestreet labelled as Chartres. This was renamed Malte in 1798 and the small stub between it and Rohan (renamed Marceau) was called Hoche. The bomb went off bottom left.