In late 1801 a large expedition quit the shores of France, bound for the Caribbean. It was being sent by Napoleon to reassert French control over the errant colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) and command had been entrusted to Napoleon’s brother-in-law, General Leclerc. The expedition was a disaster, the Europeans died in droves from Yellow Fever and the remorseless opposition of the former slaves. Before long the French were reduced to defending a few coastal towns. In their desperation to stave off final defeat they formed a unit called the Compagnie des Marins et Etrangers (the Company of Sailors and Foreigners) from stranded foreigners, compelling them to help in defending Le Cap from the armies of Dessalines. The unit was commanded by Captain Cocherel, and was composed of Americans, along with a few Scandinavians, Germans and Spanish. Its strength would seem to have been around 80 men and this is its story:

In late 1801 a large expedition quit the shores of France, bound for the Caribbean. It was being sent by Napoleon to reassert French control over the errant colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) and command had been entrusted to Napoleon’s brother-in-law, General Leclerc. The expedition was a disaster, the Europeans died in droves from Yellow Fever and the remorseless opposition of the former slaves. Before long the French were reduced to defending a few coastal towns. In their desperation to stave off final defeat they formed a unit called the Compagnie des Marins et Etrangers (the Company of Sailors and Foreigners) from stranded foreigners, compelling them to help in defending Le Cap from the armies of Dessalines. The unit was commanded by Captain Cocherel, and was composed of Americans, along with a few Scandinavians, Germans and Spanish. Its strength would seem to have been around 80 men and this is its story:

The Expedition

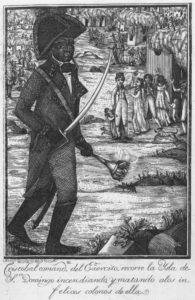

The colony had been beset by troubles in the 1790s and successive slave revolts and Spanish and British invasions had produced anarchy which was only arrested by the forceful intervention of Toussaint Louverture. This talented soldier and administrator had, by 1801, established himself as the colony’s governor but he was, in Napoleon’s view, too keen on autonomy. The Peace of Amiens would provide the First Consul with the opportunity to bring Toussaint to heel and perhaps restore the fortunes of what had been France’s most profitable colony.

The Disaster

The expeditionary force arrived off the coast of the western part of the island in February 1802 and soon scattered Toussaint’s forces. By June 1802 Toussaint had been arrested and deported to France, many of his units professed their loyalty to Leclerc and only a few rebels took to the hills. Then, when all seemed on the cusp of success, disaster struck. Yellow fever decimated the newcomers and rumours, drifting in from Guadaloupe, that the French were about to restore slavery, sparked a new rebellion under the energetic leadership of Toussaint’s lieutenants Christophe and Dessalines. Leclerc died of the fever that November and he was replaced by General Rochambeau, the vain son of the hero of the American Revolution. Rochambeau’s repressive measures exacerbated the rebellion and drove the mulatto population, who had been sympathetic to the restoration of order, and French rule, into the arms of the rebels.

Rochambeau, short of men and short of money, found his rule restricted to a handful of coastal towns including Port-Républicain (now Port-au-Prince), Le Cap, Les Cayes and Le Môle Saint-Nicolas. Frantic appeals for reinforcements largely went unheard – a handful of units trickled in. Admiral Bedout had brought in the last sizable reinforcement in January 1803 – a mixed bag of Poles, the 20th and 23rd Line, the 4th Light, 600 ex-Chouans from the jails of Normandy and the dregs from various depots and prisons on the French coast. The 89th Line arrived in May 1803, then nothing more. By the summer of 1803 the situation was desperate. At the end of June, with Britain and France again at war following the failure of the Peace of Amiens, the Royal Navy was again intercepting French shipping and blockading Rochambeau’s ports. No more reinforcements could be expected, no more food could be imported and, with Dessalines’ rebels closing in, the French and the colonists found themselves under close siege.

The Last Act

At Le Cap, the unfortunate seat of the unfortunate government, measures were taken to prepare the town, which had been burnt to the ground in 1802, for the trials to come. Inhabitants were forbidden to leave without a passport issued by Rochambeau, defences were repaired and a series of measures put in place to strengthen the garrison. One of these was to bolster the National Guard, the colony’s militia composed of colonists and residents of the town. Pressure had been mounting on the inhabitants for some time – financial demands, the confiscation of goods and the seizing of horses – then, in the spring of 1803, came increased pressure on individuals to take up arms in defence of the town. Comandant [Pascal] Sabès had the following proclamation posted on the city walls:

“The National Guard, formed up in order to oppose the incursions of the brigands and to maintain good order in the town, offers every citizen who finds himself in Le Cap security for their persons and their families, and protection of their property, and joining its ranks is therefore urged upon every citizen who is liable for such service. Everyone has his own interests to protect and it is hard to imagine that there are cowards or such selfish individuals here who rely on the bravery of others at this present time and who do not wish to share in the struggle. However, I am indignant to note that I am convinced that there are a large number of such people at Le Cap, those who do not undertake any kind of military service or respond to the alarm. In short, they are contemptible just when the occasion calls for strength and when the citizens of Le Cap should stand firm.

It is urgent that strong measures be taken against such individuals and that all citizens of Le Cap are enrolled into the ranks so that the length of time individuals are placed on guard duty is reduced and they are saved from excessive fatigue. In consequence, it is ordered that all citizens resident in Le Cap who, without legitimate motive, have not been enrolled in the National Guard must present themselves without delay before Commandant Toussard and be placed in a company for active service.

Weapons will be issued to them by the captain of the company in which they will serve.

Employees of the administrative offices will be placed in the Administrative Company. Entry in to the company of Sailors and Foreigners is reserved exclusively for those who are not French, and who find themselves temporarily in Le Cap, and sailors employed on land but who serve in the navy.

Exemption from active duty can only be obtained by those who are sick or infirm and they need to be supplied with a certificate by a medical officer of the National Guard and which states the nature of their illness or infirmity and confirms that they are not fit to serve at all or are not fit to serve for a stated period. Such a certificate will only be valid if signed by myself and by Commandant Toussard.

The most strict measures will be taken against anyone who has not acted upon these orders within three days. When this period has expired, such individuals will be arrested, condemned to prison for a month plus one month hard labour in the arsenal.

I urge all good citizens to inform me if they know of anyone seeking to evade these orders and measures will be taken against them. Seen and approved by General Clauzel.”

Little is known about the Compagnie des Marins et Etrangers (the Company of Sailors and Foreigners) but it would serve in the last few months of French rule defending Le Cap from Dessalines. It was commanded by Captain Cocherel, an officer appointed by the commandant of the National Guard, chef de battalion Toussard, and was composed of Americans, some Scandinavians, Germans and Spanish, as well as French sailors stranded ashore by the blockade. Its strength would seem to have been around 80 men.

A letter from n officer in the company has survived. It was written by a second lieutenant in the company and a man not disposed to stay until the bitter end. The author was Moses Hart, an American merchant, and in June 1803 he wrote to his superior, Captain Cocherel:

“Le Cap

from Mr Hart, sous-lieutenant in the Company of Sailors and Foreigners

to Citizen Cocherel, captain of said company

It being my intention to return to the United States, I would like to ask you to please grant me permission. I will always retain the most profound gratitude for the marks of friendship you have shown towards me. Believe that I shall not cease to wish you, and all those you command, every happiness. Greetings and respect, Moses Hart.”

The request was forwarded on by Cocherel to Toussard with the request that the request be granted and, on 1 Messidor An XI [20 June 1803] Toussard approved Hart’s leave and gave it the National Guards stamp of approval (“security and good order”).

There were a number of foreign units operating with the French in Saint Domingue. Two Polish legions, a battalion of Austrian deserters, a battalion of Swiss infantry and various depots of foreign deserters (including English sailors) were despatched to the Caribbean. This particular company was unusual as foreigners were not normally incorporated into the National Guard. It was a sign of desperation.

The unit seems to have scattered in the final fighting – no such company features in the list of units who embarked following Rochambeau’s capitulation to the Royal Navy (to save himself from Dessalines’ revenge) in November 1803. It is likely that the foreign merchants stayed on shore, whilst the sailors would have been welcome amongst the depleted crews of the French ships stranded in Le Cap’s harbour. Some of those who stayed onshore were no doubt massacred in the wave of reprisals that followed the French surrender, others might have made it eastwards to the part of Hispaniola still occupied by the French (the former Spanish possession which would become the Dominican Republic). In the dark days of 1803, this short-lived unit disappears from the footnotes of history, as does Moses Hart.

- Poles during the Napoleonic era

- Napoleon's Police

- Nelson at Naples in 1799

- Napoleon and Saint Domingue

- Voyage to America by Monsieur J P Bechaud

- Netherwood the Swede

- Napoleon's Americans

- A Plan to Put Down Slave Revolts using Native Americans

- Louis Bro in the West Indies

- Sergeant Beaudoin in Haiti

- The Death of Murat

- Napoleon in Russia

- Ireland in the 1790s

- Napoleon and Egypt

- Prisoners of War (1792 to 1815)

- Travel in Napoleonic Europe